In the words of its publisher, Territory Magazine celebrates life in Boise and the urban West. For a few years it was my favorite publication for which to write.

That’s for two reasons.

First, the range of subjects I was assigned to write about was interesting.

Second, the editor was a former journalism colleague, and I think we respected each others’ work. He didn’t have to worry about heavy edits to my stories, and I didn’t have to prove myself or worry about my work being edited with a heavy hand.

The editor was laid off and the publication went dormant at the onset of the pandemic in 2021, but I’m hopeful it will be revived in coming years.

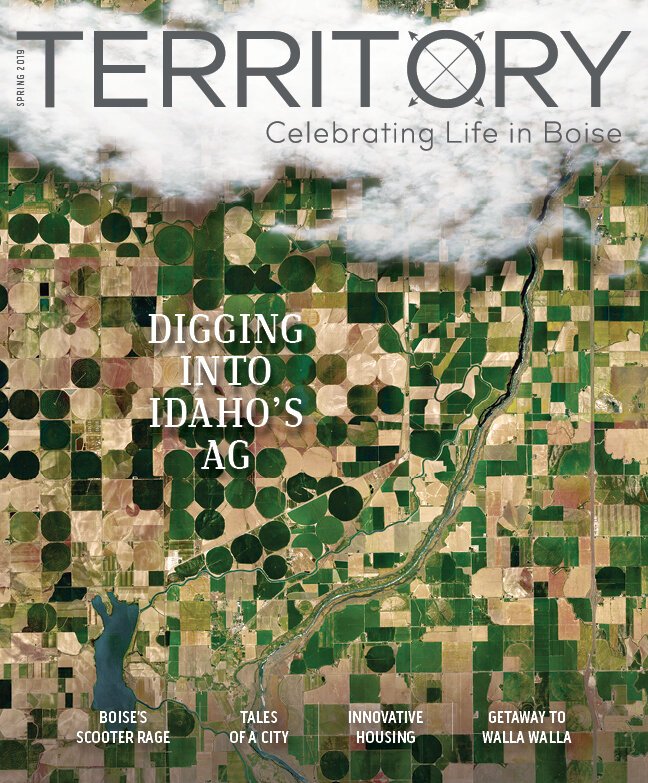

Karl Joslin is a man shaped by southern Idaho’s fertile desert soils. A third-generation farmer who was born near Salmon Falls Creek south of Twin Falls, Joslin embodies the idea that farming can be a multi-generational family affair.

“My dad was a farmer. My grandfather was a farmer. I was raised on the farm and grew up with the farm,” said the 65-year-old owner of Joslin Organic Farms during a recent tour of his properties. “I went away to college and decided it was in fact a good way for me to make a living and enjoy doing it. So, I came back to the farm, and here we are.”

Joslin specializes in organic farming and grows black, red and pinto beans he sells to Amy’s Kitchen, as well as alfalfa, wheat, corn and barley he sells primarily to a nearby organic dairy. In turn, the dairy will sell to cheese, milk and yogurt producers in the region. Cementing his position in an interrelated economic machine, Joslin also buys waste from nearby trout farmers to help fertilize his fields.

It’s all part of a massive industry that boosters say lies at the foundation of Idaho’s economy. Each year, the Idaho State Department of Agriculture estimates that Idaho growers, livestock producers and aquaculture generate $16 billion in direct and indirect spending, a figure bested only by the rapidly-growing tech sector.

“We always talk about ag as the cultural foundation of Idaho, and also the economic foundation,” said Idaho State Department of Agriculture Chief Operating Officer Chanel Tewalt. “In whatever community you go to, whether it’s Boise or Burley, which is very ag-centric, you’re going to have ag dollars flowing through the economy, and I hope some cultural recognition of that.”

Read more of “Digging into Idaho’s Ag” written for Territory Magazine.

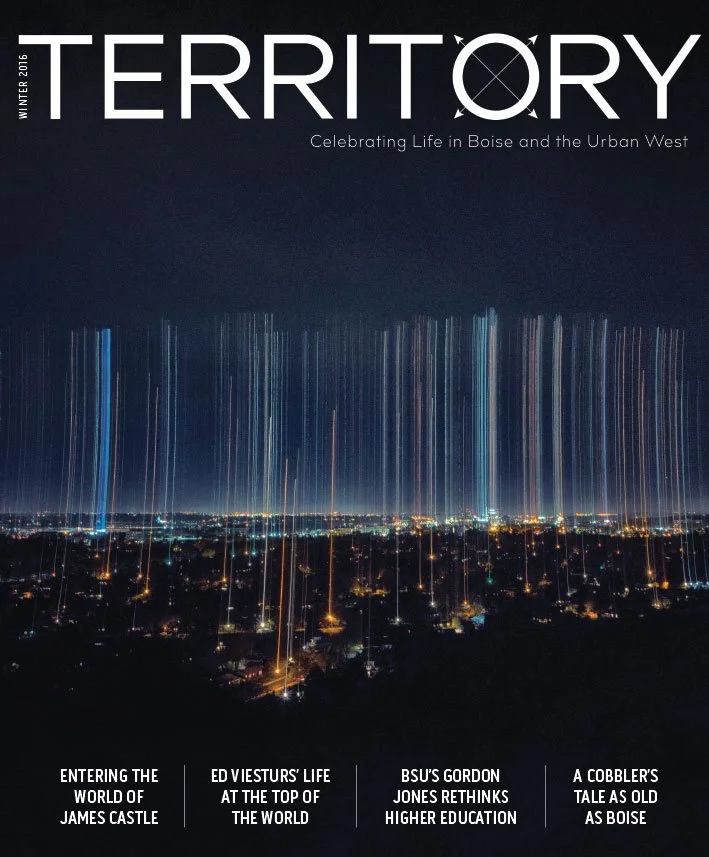

Gordon Jones is a student and teacher, hockey player and skier, freethinker and pragmatist. But perhaps most of all, he’s a man with a penchant for thinking outside the box.

In 2015 Jones traded Harvard for Boise State to help rethink higher education. He appears poised to continue on an already-developing trajectory of success.

“I love the idea of challenging conventional wisdom,” he said during a late-July interview in Boise. “That type of thinking fuels me.”

Jones is the inaugural dean of Boise State’s new College of Innovation and Design, a difficult-to-define entity that exists along the fault lines of traditional education. It’s a combination of degree-track programs, professional certificates and badges that show records of accomplishment and competencies. It’s all designed to synthesize the university’s various academic disciplines and give students a competitive edge in today’s rapidly evolving professional marketplace.

Twenty years ago, Boise kayaker Paul Collins had a dream to build a small wave on the Boise River where kayakers could safely practice and play. That whimsy turned into a $25 million collection of facilities that includes 66 acres of flat-water paddling, waterfront park space and a state-of-the-art, in-river whitewater park that’s still growing.

“I didn’t imagine what we have, but I dreamt about it,” said Collins, an orthopedic surgeon based in Boise. “I couldn’t’ tell you the specific size, depth, how much concrete or where the waves would be. But I had a dream that we would have a place to play, and we do.”

Collins continues to work as part of a group called Friends of the Park, which raises money for the still-expanding riverside facilities in Boise’s West End. Although he and a handful of others first introduced the notion of a river park to the community, it has grown far beyond their original vision. Major financial stakeholders now also include the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation, J.R. Simplot Foundation and City of Boise, each having contributed millions to transform a neglected part of the city into what may well be the nation’s premier outdoor aquatics recreation facility.

It was a stunning, sunny spring morning in Boise, Idaho’s Liberty Park near the St. Alphonsus medical campus, and two dozen people gathered with the promise of putting roots in the Earth.

A day and a half of rain had just concluded. Tilled soil was wet and stuck to shoes in big, muddy clumps. A group of women wearing bright blue, orange, yellow and purple head-scarves sat on the dirt, basking in the strong spring sun and scent of a just-passed storm.

Mahamud Kuso wore a blue button-up shirt and sat near the edge of the field with some other men. He spoke some English, but after several probing questions from a reporter flagged down a friend to translate his native Swahili.

He waved an arm toward the 2 acres of tilled soil where refugees of various nationalities were poking around a grid delineated by orange-painted wood stakes. In his native Kenya, he said, one person would farm an entire area that size, and that would be their main source of income. In Boise, the 3 square-meters that will be allotted to his entire family is comparatively tiny.

“You don’t have time to farm that much anyway because you have to work,” he said. “Back home there is less work, so you have to focus on farming for your daily bread.”

The community garden is an opportunity for refugees from diverse cultures and backgrounds to come together and nurture a sense of place, pride and fraternity. It’s also a great way to produce local food. On another level, though, it’s a fitting metaphor for refugee resettlement in the Treasure Valley. Families and people of various ethnicities were forced from their homelands and are looking for a place to put roots in the earth.

Read more of this feature at the Territory magazine website.

Download a pdf of the story.